There are many terms used in the literature, online, and by educators to describe the potentially negative effects of working in the helping professions: burnout, compassion fatigue, empathic strain, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious trauma, to name a few.

The use of so many terms is confusing for several reasons. First, there is no consensus about what these terms actually mean. Second, there is no agreement about what phenomena they are describing. Lastly, these terms are often used inconsistently and interchangeably.

This confusion makes conducting a literature search, measuring and comparing incidence rates, or offering evidence-based best practice recommendations an impossible task.

This nomenclature problem is not new. It was originally highlighted in 1997 by a pioneer in the field, Dr. Beth Stamm. On the very first page of her book Secondary Traumatic Stress: Self-care Issues for Clinicians, Researchers, and Educators, she writes:

“The great controversy about helping-induced trauma is not “can it happen?” but “what shall we call it?”

The emergence of compassion fatigue

Over the past 25 years, the term compassion fatigue has become widely recognized. It is used to describe the profound emotional and physical exhaustion that helping professionals and caregivers can develop over the course of their career. This exhaustion can be felt towards the people they serve, their colleagues, or their loved ones.

The term compassion fatigue, in particular, has been the subject of lively debates between researchers.

Compassion fatigue was first coined by Carla Joinson in 1992. She used the term to describe the loss of “the ability to nurture” among nurses. It was then adopted by Dr. Charles Figley and his colleagues in a series of books and articles exploring the intersection between secondary traumatic stress and burnout. This led to an emergence of much needed research in the area of provider impairment..

Originally, Dr. Figley suggested that compassion fatigue was the result of burnout and second-hand exposure to trauma. This combination could lead to service providers developing the syndrome compassion fatigue. Dr. Figley chose to use the term compassion fatigue in hopes that it would be less pathologizing than the term secondary traumatic stress. It might also increase people’s openness to the issues that the term was describing.

Vicarious traumatization and compassion stress are other terms that researchers in the field were using. These terms attempted to capture the subtle, but important differences between the factors that cause provider impairment.

It is important to note that, as with all emerging areas of research, the intent was to provide a framework for a phenomenon that was poorly recognized. The goal was to raise awareness and develop a field of research on strategies to reduce provider impairment.

Counterpoint: “compassion is not fatiguing”

Over time, pushback emerged about the use of the term compassion fatigue among followers of Buddhism and those studying the field of compassion and self-compassion. They argued that compassion was not, in fact, an exhaustible resource. Therefore, it could not be “fatigued.” They suggested that the terms empathic strain or empathic distress were more accurate.

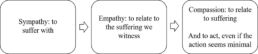

To understand their argument, it is useful to clarify the difference between three terms: sympathy, empathy, and compassion.

Sympathy-Empathy-Compassion Continuum (Singer 2018)

Image source: Thibeault, R., 2020 Compassion & Well-Being Webinar, CAOT

What is sympathy?

Sympathy is defined as “the ability to take part in someone else’s feelings, mostly by feeling sorrowful about their misfortune.” Sympathy is about suffering alongside the other person.

What about empathy?

Empathy has been described as “the ability to understand other people’s feelings as if we were having them ourselves.” Empathy is an essential human trait that allows us to relate and connect with others.

Empathy is not something to be avoided. However, when working in high stress, trauma-exposed environments, empathy can contribute to provider distress.

Some of the lead researchers on empathy said it best:

“While shared happiness certainly is a very pleasant state, the sharing of suffering can at times be difficult, especially when the self-other distinction becomes blurred. Such a form of shared distress can be especially challenging for persons working in helping professions […]” (Singer & Klimecki, 2014)

Compassion is a verb

Compassion is our ability to recognize the suffering of others and is accompanied by the desire to relieve or lessen that suffering.

What is particularly interesting about compassion is that there is an action element to the experience. Singer and Klimecki (2014) have explained that “[…] it is characterized by feelings of warmth, concern and care for the other, as well as a strong motivation to improve the other’s wellbeing. Compassion is feeling for and not feeling with the other.”

The Neuroscience

In the past decade, neuroscientists performing brain imaging research have explored the neural pathways of compassion and empathy.

They have discovered that feelings of empathy can generate activity in our pain centers – but that feelings of compassion do not. Instead, research suggests that feelings of compassion stimulate another brain center which they believe is related to positive emotions (Singer & Klimecki, 2014).

Should we go to empathy or compassion?

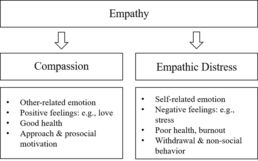

Research into the neuroscience of compassion and empathy also suggests that we have a decision point when experiencing an empathic response: “[…] an empathic response to suffering can result in two kinds of reactions: empathic distress […] and compassion […]” (Singer & Klimecki, 2014).

Image source: Singer & Klimecki, 2014.

Compassion can be learned

Emotional regulation training, self-awareness, loving-kindness meditation and other forms of mental practices can teach us to shift from empathy to compassion. Neuroscientist Richard Davidson has said: “We are neurologically wired for compassion in the same way we are wired for language. […] But in both cases, we need to cultivate our biological basis with examples and experiences” (quoted in Thibeault, R., 2020).

In other words, although we are biologically wired to experience compassion, we need to build and strengthen those brain pathways. Just like a child needs to learn how to speak through interaction with other humans.

Conclusion

As a result of these recent findings, it appears that using the terms empathic strain or empathic distress are more accurate than using compassion fatigue. Using the term empathic strain points us in the direction of concrete strategies that can be developed over time.

Therefore, it is recommended that educators and researchers shift to using these more accurate terms.

Suggested Resources

Compassion & Well-Being webinar presented by Thibeault, R., and offered by the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (2020).

Compassionomics: The Revolutionary Scientific Evidence that Caring Makes a Difference book by Trzeciak, S. & Mazzarelli, A. (2019).

Richard Davidson: A Neuroscientist on Love and Learning podcast episode hosted by Tippett, K., on On Being. (2019).

This is How We Can Train Ourselves to Become More Compassionate article by Jacobs, J., on Thrive Global. (2020).

Sources

Joinson C. (1992). Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing, 22(4), 116-121.

Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2012). Empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue? Integrating findings from empathy research in psychology and social neuroscience. In B. Oakley, A. Knafo, G. Madhavan, & D. S. Wilson (Eds.), Pathological altruism (pp. 368–383). Oxford University Press.

Singer, T., & Klimecki, O. M. (2014). Empathy and compassion. Current biology : CB, 24(18), R875–R878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.054

Stamm, B. H. (Ed.). (1995). Secondary traumatic stress: Self-care issues for clinicians, researchers, and educators. Baltimore, MD: The Sidran Press.

Walsh, C. R., Mathieu, F., & Hendricks, A. (2017). Report from the Secondary Traumatic Stress San Diego Think Tank. Traumatology, 23(2), 124-128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/trm0000124